1900s-1920s

How Lightning Became a Thriving Community

Lightning was located just west of downtown. It was an attractive location for companies to set up shop and for workers to live near their employers, given how close it was to where Atlanta’s major rail lines converged.

During this period, businessmen had opened up factories that made everything from brooms to caskets. As workers moved into the neighborhood, pastors opened churches, grocers sold fresh vegetables, and a school opened its doors. Lightning was on the rise.

“People got around by following the railroad tracks. The streets, pretty much every street that ran east and west would take you to the tracks.”

Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, 1911

This map shows city blocks full of dwellings, churches, factories, and other assets — all of which helped turn Lightning into a bustling community.“If there were another low-income industrial community that would mirror Lightning, it would be Cabbagetown.”

The Atlanta Casket Company, located at 194 Elliott Street, was one of several factories located near the railroad tracks on the neighborhood’s eastern edge.Several different Black churches, including Amanda Flipper Memorial Temple, opened their doors in the early 1900s. Amanda Flipper was named after the wife of Joseph Simeon Flipper, an African Methodist Episcopal church bishop who had served as Morris Brown College’s third president.In the early 1900s, Rock Street was home to a free kindergarten named after Mary Raoul, the wife of railroad tycoon William Greene Raoul. It was one several opened across the city by the Atlanta Free Kindergarten Association. Schools like the one at Rock Street helped the association’s president, Nellie Peters Black, convince Atlanta's public school system to add kindergarten classes.1930s-1950s

How Federal Officials Devalued Lightning

Over the course of the 20th century, government officials enacted policies that harmed Black people and the places where they lived. Lightning suffered because of these policies.

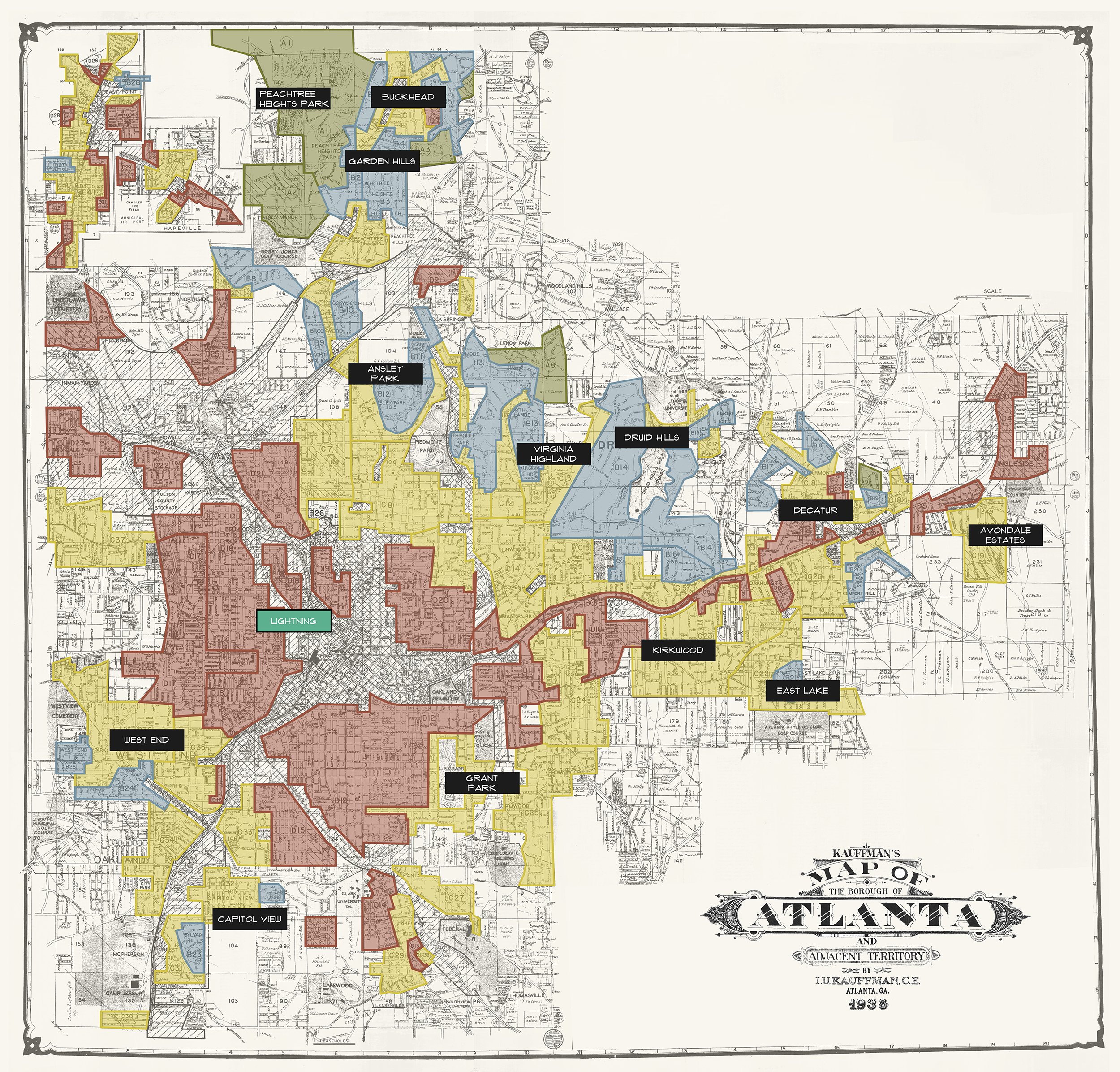

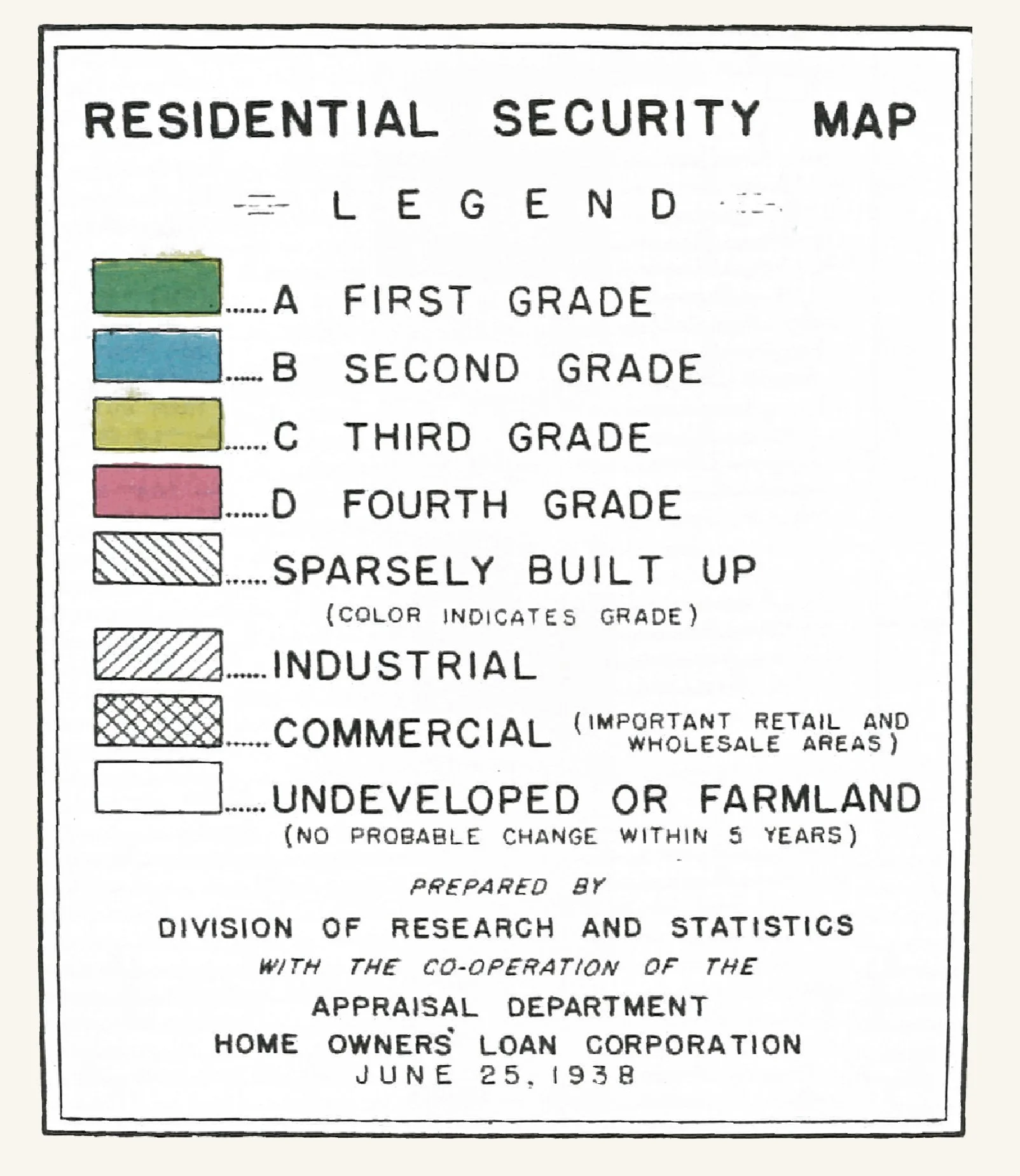

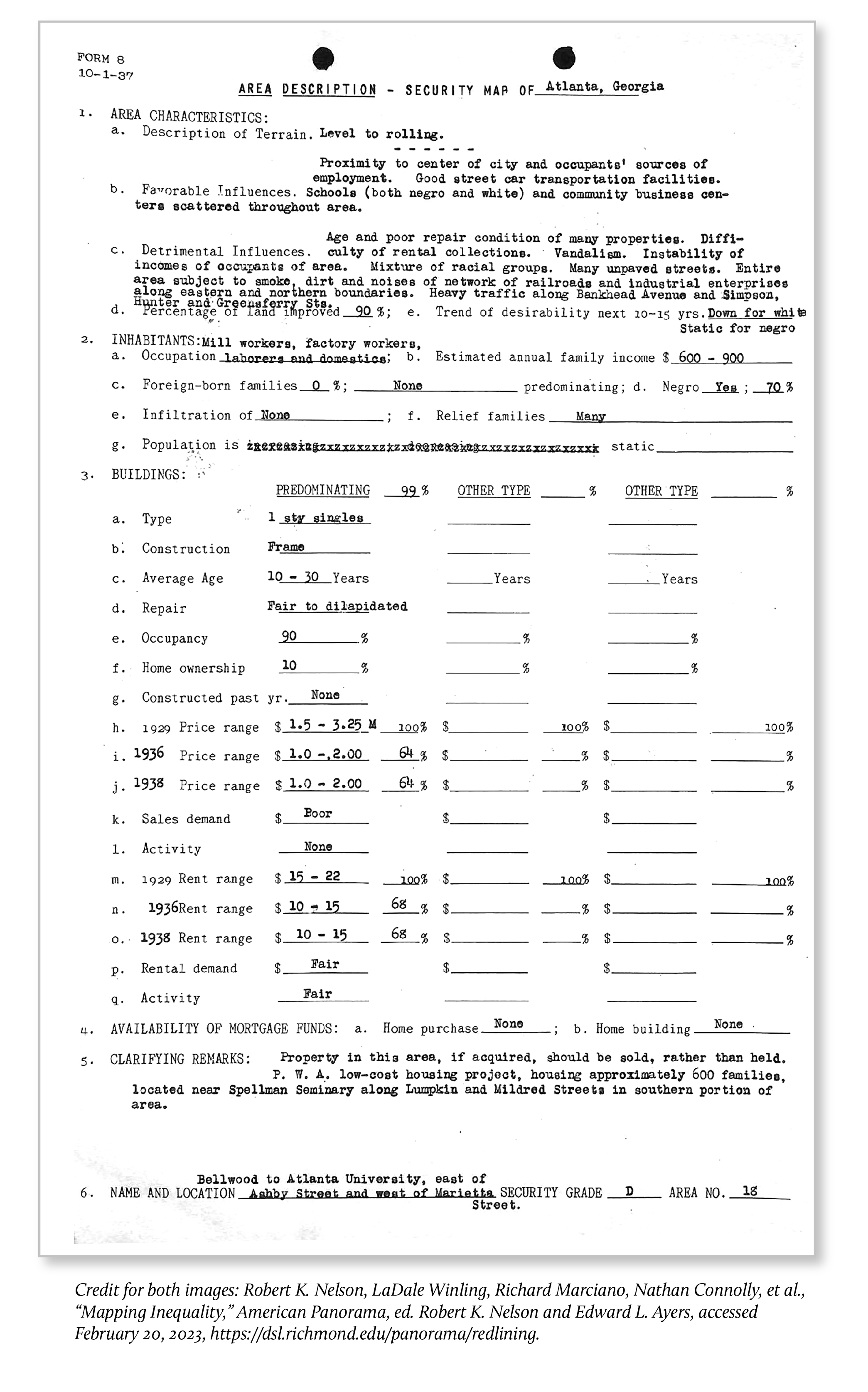

In the 1930s, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s administration created residential loan policies to help homeowners struggling during the Great Depression. Federal officials outlined neighborhoods in different colors to signify the risk of defaulting on those loans. Most of America’s Black neighborhoods were shaded in red, meaning the riskiest areas. The practice of redlining devalued property in the neighborhood.

Redlining in Action, 1938

This map, created by the federal government’s Home Owners' Loan Corporation, designated the riskiness of loans using a color-coded index. Many of Atlanta’s Black neighborhoods, including Lightning, were shaded in red, denoting the highest risk for a loan. It became the basis for denying loans to potential homeowners in those areas.Courtesy, Georgia Archives, Vanishing Georgia Collection, ful0638.

“My granddaddy bought that first house on Thurmond Street. I was born there in 1938. Most of the streets, including Thurmond, were made of dirt. That house was brick. It had a porch. There was nine [kids], my momma, and my daddy. Everybody was over there. Everyone slept wherever they could.”

Even though Lightning had a great location near downtown, surveyors focused on the area’s unpaved streets and the presence of smoke from nearby industry. They noted that the “mixture of racial groups” was a “detrimental influence” to the area. "Property in this area, if acquired, should be sold, rather than held,” surveyors wrote.Discriminatory lending not only led to depressed property values in Lightning. It also paved the way for developers to build projects that no one wanted to live around. In the 1940s, Atlanta officials opened the city’s only trash incinerator in Lightning.In the upper left of this photo from 1933, you can see bombers flying toward Lightning on a day with clear skies. While Lightning always had some industry, redlining made it easier to place more buildings that spewed pollution, degrading the neighborhood's air quality.Courtesy, Georgia Archives, Vanishing Georgia Collection, ful0638.

After garbage trucks hauled waste to the facility on Magnolia Street, sanitation workers burned the trash, causing toxic fumes to spew across the neighborhood. City regulators failed to control those emissions, even though those pollutants were harmful to residents’ health. “They burned trash twice a day. And you inhaled that twice a day. You could see it hovering in the air.”

1950s-1960s

How Planners Drafted a Future Without Lightning

Atlanta officials thought urban renewal might bring new life to disinvested pockets of the city. But their hopes were dashed.

While city planners sought funding from federal anti-poverty initiatives, President Richard Nixon slashed the budget for programs designed to help Lightning. Without additional funding to improve conditions, city and state officials would soon consider plans to redevelop Lightning. A report had been commissioned on the best place to build a new stadium for the Braves ahead of their relocation from Milwaukee. The top location that emerged was in Washington-Rawson, a southeast Atlanta neighborhood near the Georgia State Capitol. The runner-up: Lightning.

How Planners Drafted a Future Without Lightning

Atlanta planners created the "ultimate development" map for the heart of the city. They described Lightning as an "area of possible expansion west of the CBD" — the acronym for the Central Business District. “Some elders were locked in. They had nowhere else to go.”

These photos show Lightning community members hanging out under shaded trees, at the Blue Chip shoe shine parlor, and outside a grocery store.By the late 1960s, city officials had spent little on funding spaces where children could play in Lightning. There was a single playground with a pool. Beyond that, teenagers hung out on the porch of a neighborhood community center. Children also explored the industrial sites in the neighborhood.“We concluded that once Lightning was in view of developers, there appeared to be a real disinvestment in the community, to the point where it became blighted and an eyesore for downtown. It made it easier to come back and displace the community.”

1970s-1980s

How Officials Pressured Landowners to Sell Property

In the 1970s, Gov. Jimmy Carter announced the construction of the Georgia World Congress Center on the west side of downtown. Once the first phase was complete, state officials set their sights on expanding the campus west into Lightning.

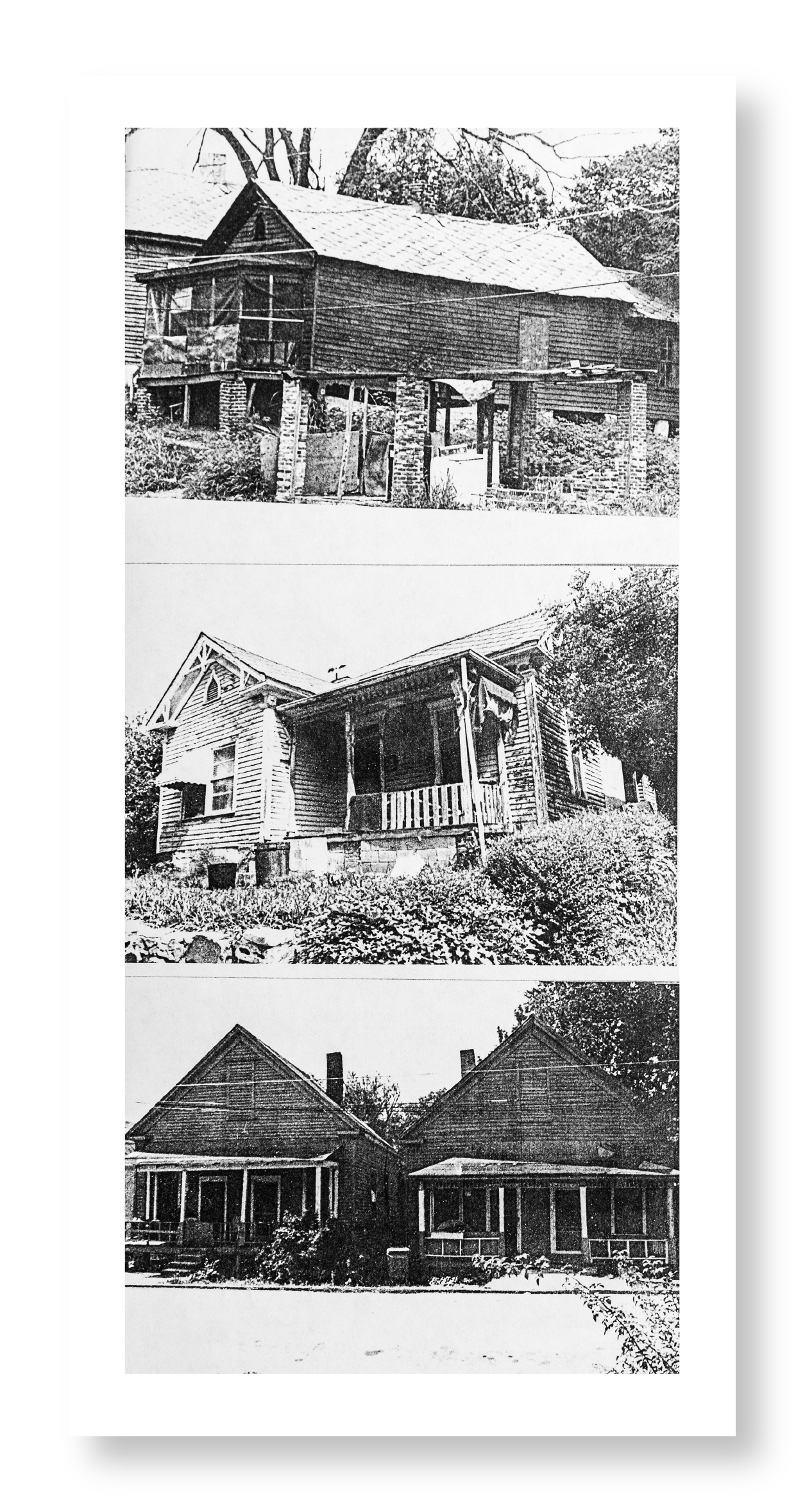

To expand the convention hall, developers first acquired four blocks of the east side of Lightning. Some residents saw the project as a threat to Lightning’s very existence. As older residents passed away, children inherited their homes without intention of resettling there. Blocks grew vacant. Real estate speculators knocked on doors to buy out residents. By the 1980s, city planners — who had deemed the majority of Lightning’s rental housing “uninhabitable” thanks to absentee landlords — called for the relocation of the remaining families. Then came the Georgia Dome, touted as one of the nation’s largest arenas of its day.

The State Moves Ahead

Pictured here is a sketch for the state’s expansion plans, which later included multiple phases of building out the Georgia World Congress Center and a new home for the Atlanta Falcons. “My parents held out. Everyone in Atlanta knew they were buying us out. They didn’t want to give people in Lightning a fair price. They wanted the land. They were trying to run us out. Sell the home — or else.”

Lightning homeowner Tillman Ward and other residents in the neighborhood were pressured to sell their homes to the state — or face the seizure of the land through the use of eminent domain. Below is a photo of Ward’s house on Rock Street. In April 1988, a real estate firm, Barber & Company, sent Ward a letter to inform him that the state planned to acquire the house.The following month, Ward and other Lightning residents requested a meeting with Gov. Joe Frank Harris to discuss the plan to relocate residents. Instead of meeting with Ward, Harris’s administration moved forward with efforts to condemn his property. “The people who were impacted the most were considered the least,” Ward told local reporters.“The state of Georgia, for the most part, came and did what I would call a taking… there was very little, if any, negotiation that was going on at all. People were only offered what the state was willing to pay. Again, no negotiation.”

Here, you can see different signs created by neighborhood residents fighting to save Lightning.The photo of the person praying was taken at a meeting held in 1987 at Mount Vernon Baptist Church. The church was one of the only houses of worship that avoided displacement. Decades later, city officials bought the property for $14.5 million so they could build the Mercedes-Benz Stadium on that land.1990s-Present

How We Erased Lightning from Our City’s History

Residents sold their homes. Pastors relocated their churches. Lightning was on the verge of disappearing for good. But one local activist tried to preserve its history.

Sister Hanifya Ali, a community organizer in Vine City, called for a “marker, monument, or other suitable commemoration” to mark the “cultural and historical contributions of Lightning, which shall cease its existence once the buyout is completed.”

Present Day

When fans file into Mercedes-Benz Stadium, few know how much of Atlanta’s history was sacrificed in the name of the city’s dreams of hosting events like the Super Bowl or the World Cup.“It’s rare to run into someone who knows Lightning. They usually just associate it with the weather.”

Sister Ali tried to preserve one of Lightning’s last houses. The Atlanta Preservation Center recognized the importance of her efforts.But Dan Graveline, the executive director of the Georgia World Congress Center, informed her that the homes would be demolished. During her campaign, Ali was treated with disregard by people attempting to displace Lightning residents, as can be seen in this letter from Rankin Smith, chairman of the Atlanta Falcons’ board.Millions of people flocked to the Georgia Dome for Falcons games, two Super Bowls, and the Atlanta Olympics. The stadium elevated Atlanta’s international image. But the city’s profile ascended at the cost of families who were displaced across the region. Twenty-five years after Lightning was destroyed, Atlanta Falcons owner Arthur Blank convinced the city to help fund a new stadium. The Dupree sisters look on at the Georgia World Congress Center, which was built on the community where they were raised.